Internalization Architecture

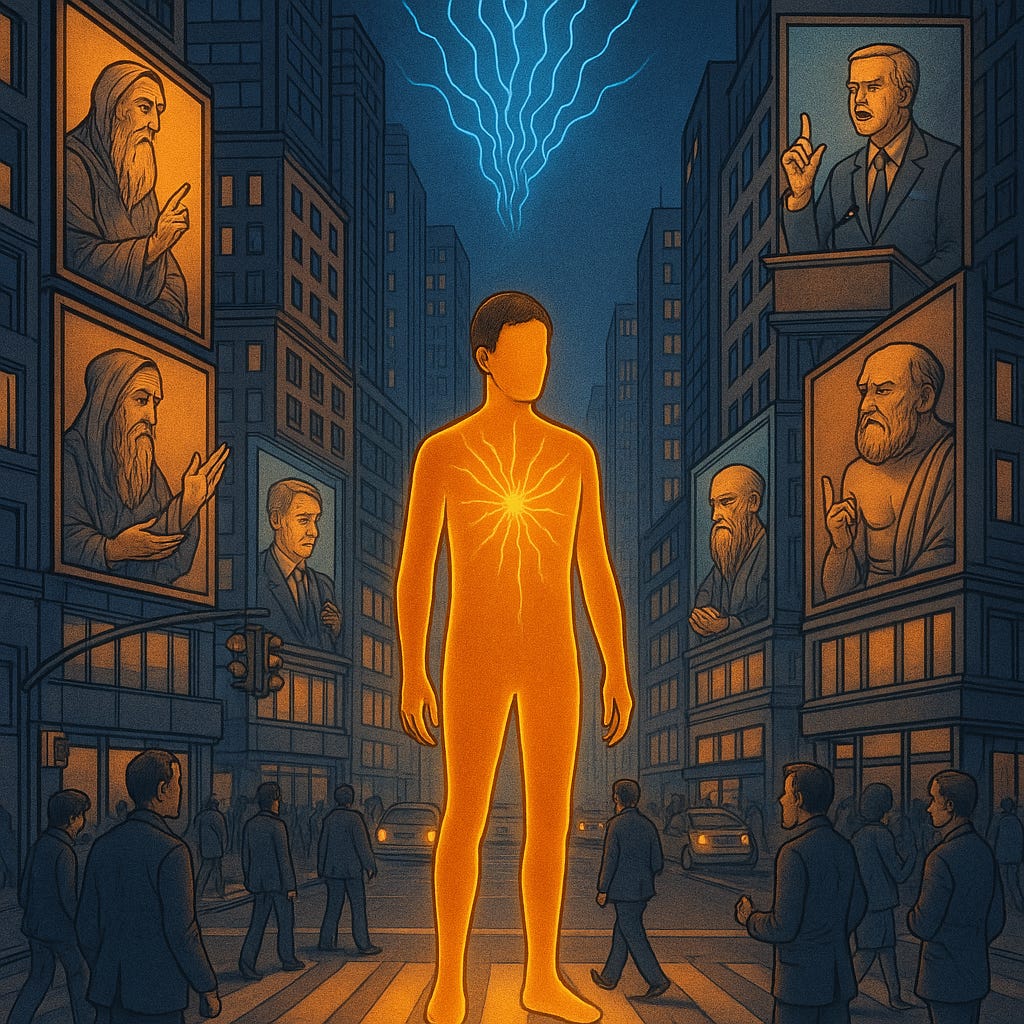

And the Memeforms we use to fill ourselves

An Internalization Architecture is the living, adaptive set of cognitive-emotional structures through which a person interprets, organizes, and integrates experiences into a meaningful inner world.

Rather than assuming a single "correct" way of processing the world, an Internalization Architecture acknowledges the profound variability between individuals. It reflects the reality that the human mind builds meaning relationally, depending on a person's unique neurocognitive patterns, emotional capacities, and social and existential conditions.

This concept is crucial for understanding how we form identities, how we relate to others, how we make decisions, and how we build resilience in an overwhelming and often contradictory world (Siegel, 2012; Perry, 2006).

Foundational Premises

Every human being develops some form of Internalization Architecture.

There are no "empty" or "neutral" minds; we are shaped continuously by what we encounter (Vygotsky, 1978).Internalization Architectures are inherently diverse and dynamic.

No two individuals have identical architectures, and any given individual's architecture can shift over time (Fischer & Bidell, 2006).Mental health, neurodivergence, trauma, and lived experience profoundly influence Internalization Architectures.

Differences such as depression, ADHD, autism, CPTSD, chronic grief, or existential crisis are not deviations from the model, but natural variations it must account for (Grandin, 2009; van der Kolk, 2014).The goal is not perfection or uniformity.

The goal is enough coherence to sustain meaning, agency, and connection, however that coherence is uniquely formed.

The Six Structures Of Internalization Architectures

The selection of the six Integrative Structures arose from a synthesis of interdisciplinary research in developmental psychology, trauma studies, narrative theory, systems thinking, and neurodivergence advocacy.

I began by asking: What are the essential internal functions that must exist, in some form, for a person to experience themselves as an agentic being embedded in a meaningful world? This led me to prioritize structures that not only describe cognitive processing, but also emotional regulation, symbolic mediation, ethical orientation, ontological stability, and social resonance.

Each structure was distilled from extensive empirical and theoretical work done by experts across multiple disciplines. I will mention only the those that were most influential to me, but I would urge everyone reading this to explore these domains extensively in order to form their own understanding.

Narrative Coherence draws from narrative identity research showing the role of autobiographical storytelling in meaning-making and psychological integration (McAdams, 2001).

Affective Regulation is foundational in developmental psychology and trauma recovery, reflecting how emotional states are navigated and stabilized (Schore, 2012).

Normative Guidance is rooted in social cognitive theory, ethics, and cultural anthropology, emphasizing the internalization of moral and behavioral frameworks (Bandura, 1986).

Symbolic Translation is informed by cognitive linguistics, semiotics, and studies of symbolic functioning, including variations like aphantasia or anauralia (Zeman et al., 2015).

Ontological Anchoring reflects existential psychology, particularly the need for a stable sense of reality and meaningful existence (Frankl, 1959).

Coordination Resonance is based on systems theory and relational sociology, recognizing the necessity of felt connection to broader social and ecological systems (Capra, 1996; Emirbayer, 1997).

In developing this model, I prioritized inclusivity, ensuring that these structures allow for profound individual variation, adaptation, and resilience across the spectrum of neurotypical and neurodivergent experiences.

These are the six major structures through which experience is organized.

Each one can be robust, fragmented, latent, nonlinear, or uniquely expressed depending on the person.

Integrative Structure

1. Narrative Coherence :The degree to which a person organizes experiences into a self-story. Some may have a strong ongoing narrative; others experience nonlinear, fragmented, or evolving narratives. Narrative strength may fluctuate with trauma, depression, or neurodivergence (McAdams, 2001).

2. Affective Regulation The ability to recognize, manage, and respond to emotional states. This regulation can be instinctive, learned, impaired, or inconsistent. It may be shaped by attachment history, nervous system conditioning, and developmental factors (Schore, 2012; van der Kolk, 2014).

3. Normative Guidance The sense of internal "rightness," including ethics, values, and social expectations. For some, this guidance is clear and deeply rooted; for others, it is fragmented, externally dependent, or shifting. Executive function difficulties may influence this domain (Bandura, 1986).

4. Symbolic Translation The process of connecting internal experiences with external symbols (language, art, ritual, metaphor). Variations such as aphantasia (lack of visual imagery) or anauralia (lack of internal monologue) significantly affect this domain (Zeman et al., 2015).

5. Ontological Anchoring The internal sense of what is real, sacred, important, or fundamentally true. Existential crises, dissociation, or deep trauma can destabilize this anchoring; spirituality, philosophy, and community can reinforce it (Frankl, 1959).

6. Coordination Resonance The felt capacity to connect one's internal world to larger systems (family, culture, society, cosmos). This resonance can be empowering, fragmented, absent, or even aversive depending on history with collective belonging or harm (Capra, 1996).

Important:

An Internalization Architecture does not have to have fully functional or fully accessible structures in all six domains to be valid.

Each individual will have their own constellation of strengths, absences, adaptations, and creative compensations.

Dynamic Variations and Access

Because we live dynamic lives in dynamic bodies, Internalization Architectures are not static.

A person might have strong Narrative Coherence when feeling healthy, and fragmented coherence during a depressive episode (McAdams, 2001; van der Kolk, 2014).

Someone might experience deep Symbolic Translation through music even if they have no visual imagination (Zeman et al., 2015).

Another might have impaired Affective Regulation after trauma but regain it through therapy, somatic practices, or supportive environments (Porges, 2011).

This model views adaptation not as a defect but as a form of resilience.

It also acknowledges that external factors (poverty, systemic injustice, colonization, media saturation) actively stress and strain Internalization Architectures (Freire, 1970).

The world does not only present empowering patterns; it bombards people with contradictory, harmful, or dehumanizing patterns that challenge emotional regulation, ontological security, and normative guidance.

Memeforms and Memeplexes

Memeforms and memeplexes are the external stories, ideas, norms, or belief systems that offer templates for constructing or modifying one's Internalization Architecture. Memeforms are a subset of memes (units of culture) that are fit for internalization.

Examples include:

Religious frameworks

National myths

Political ideologies

Family systems

Popular media narratives

Consumer identity marketing

Trauma narratives

Some memeplexes are comprehensive, others are fragmented.

Some are empowering, others are disempowering, coercive, or manipulative.

Importantly, the intake of Memeforms interacts with the existing architecture. Different people will absorb, modify, reject, or reinterpret the same external memeform depending on their internal landscape (Fischer & Bidell, 2006).

As might be clear to some already, it is possible to intentionally construct a comprehensive Pattern of Internalization (the resulting pattern of internalized memeforms), and depending on how this pattern is designed, it can result in a range of fundamental outcomes once internalized, from the harmful and suppressive, to the compassionate and empowering.

Fragmented Memeplexes

Many external memeplexes are incomplete or contradictory. When internalized:

They may leave gaps in narrative coherence.

They may overload affective regulation.

They may destabilize ontological anchoring.

When encountering a memeform or memeplex, critical discernment is essential.

Conflict of Memeforms

One of the most important elements of analyzing memeforms is recognizing that external memeforms can conflict with one another (Meadows, 2008; Graeber, 2004). In any given moment, people are exposed to numerous external ideas, systems, and stories that aim to shape their internal processes. These influences (from media, politics, culture, religion, and family) often do not align neatly. Instead, they may contradict each other or compete for the same psychological space within the individual's Internalization Architecture (Habermas, 1984).

For example, consider two conflicting patterns:

A memeplex that asserts personal success and ambition as the ultimate goals of life, often rooted in capitalist ideals of individualism and meritocracy (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009).

A second memeplex that promotes community care, collective responsibility, and social equality, central to more collectivist or anarchist ideologies (Graeber, 2004).

These two memeplexes cannot coexist peacefully without creating cognitive dissonance, inner conflict, or emotional turmoil, especially within the Normative Guidance and Narrative Coherence structures of the architecture. Each offers a fundamentally different answer to the question of what is "right" or "meaningful" — one emphasizing personal achievement, the other emphasizing communal well-being. When internalized simultaneously, these conflicting patterns often leave individuals torn between competing ideals, unsure where to direct their energies, or experiencing guilt when acting in ways that contradict one internalized value (Lukes, 2005).

Conflicting patterns also distort other components of the Internalization Architecture:

Affective Regulation can become destabilized, leading to anxiety, guilt, or persistent feelings of inadequacy as different internalized values clash.

Ontological Anchoring can fracture, causing individuals to question the very nature of reality and what is considered "real" or "sacred" (Meadows, 2008).

Coordination Resonance can weaken, making it difficult for individuals to align with larger collective efforts, undermining social coordination and increasing feelings of isolation (Habermas, 1984).

Resolving such internal conflicts requires individuals to engage in a process of conscious integration. This involves actively identifying conflicting patterns, critically assessing their origins, and deciding which elements to retain, transform, or reject. Without this conscious effort, individuals risk becoming passive absorbers of external contradictions, often at the cost of their psychological coherence, emotional stability, and volitional clarity (Scott, 2004).

The Importance of Compassionate Internalization

In a world of overwhelming information and social pressure, our Internalization Architecture is both a source of inner sovereignty and a site of deep vulnerability.

We must develop the critical capacity to analyze external patterns before internalizing them.

And equally, we must extend compassion toward ourselves and others when our architectures bear the marks of struggle, adaptation, and imperfect integration.

There is no final, perfected architecture, only an ongoing weaving of meaning, agency, and connection from the threads available to us.

A Basic Method for Inspecting Memeforms and Memeplexes

Before accepting a new idea, narrative, or belief system into your architecture, ask:

Narrative:

How does this pattern try to shape my story of self? What identity does it encourage me to adopt?Affect:

What emotional states does it invoke or suppress? Does it weaponize fear, shame, or helplessness?Norms:

What moral framework is embedded in it? Whose interests do these "shoulds" serve?Symbols:

What images, rituals, or language does it use to link inner and outer meaning? Are they clear, manipulative, alienating?Reality:

What picture of "reality" does it demand I accept? Does it allow for complexity and nuance?Connection:

How does it position me relative to others, systems, communities? Does it foster belonging, division, hierarchy, or dependency?

If a memeform feels empowering, generative, coherent, and respectful of your agency, it may be a good thread to weave.

If it feels coercive, disorienting, alienating, or flattening, it deserves much deeper questioning.

References

Capra, F. (1996). The web of life: A new scientific understanding of living systems. Anchor Books.

Emirbayer, M. (1997). Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 281–317.

Fischer, K. W., & Bidell, T. R. (2006). Dynamic development of action and thought. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology (6th ed., Vol. 1). Wiley.

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man's search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Bloomsbury Academic.

Graeber, D. (2004). Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Prickly Paradigm Press.

Grandin, T. (2009). Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism. Vintage.

Habermas, J. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action: Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Beacon Press.

Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A Radical View (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100–122.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Nitzan, J., & Bichler, S. (2009). Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder. Routledge.

Perry, B. D. (2006). Fear and learning: Trauma-related factors in the adult education process. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 110, 21–27.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Schore, A. N. (2012). The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Scott, W. R. (2004). Institutional Theory: Contributing to a Theoretical Research Program. In Great Minds in Management.Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. Guilford Press.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Zeman, A., Dewar, M., & Della Sala, S. (2015). Lives without imagery: Congenital aphantasia. Cortex, 73, 378–380.